Antoni Gaudí Biography: A Short Journey Through His Life and Iconic Buildings

Antoni Gaudí was more than an architect—he was a dreamer, a craftsman, and a revolutionary mind who transformed the way we see space, form, and faith. Born in 1852 in Reus, Catalonia, he fused geometry, symbolism, and the beauty of the natural world to create structures that feel alive. His legacy, immortalized in works like Park Güell, Casa Batlló, and the still-unfinished Sagrada Familia, has turned Barcelona into an open-air museum of imagination. This article explores Gaudí’s remarkable life, his most iconic works, and the mystical connection between his art and the world around him.

Gaudí’s Early Years: Nature, Family, and Form

Antoni Gaudí i Cornet was born on June 25, 1852, in the Catalan city of Reus. From his earliest days, he was deeply connected to craftsmanship and nature—two elements that would later define his architectural vision. His father, Francesc Gaudí, was a talented boilermaker, skilled in shaping metal into complex volumetric forms. Observing this process as a child ignited Antoni’s spatial imagination.

“I have this ability to see space because I am the son, grandson, and great-grandson of boilermakers”

Gaudí would later affirm, attributing his geometric instinct to his family trade.

His childhood was often marked by illness and forced him to spend time in his country house in Ruidoms. Living between Reus and the family country house in Riudoms, Gaudí absorbed the surrounding nature: the twisted trunks of Mediterranean pines, the rocky silhouettes of the Prades Mountains, and the tranquil geometry of leaves and seashells. These forms would resurface in his buildings decades later.

Gaudí’s education began at a local school run by Francesc Berenguer, whose son would later collaborate with him on several projects. In 1863, he enrolled at the Escolas Pías of Reus, where he met lifelong friends Josep Ribera Sans and Eduard Toda i Güell. These relationships, along with his love for nature and crafts, shaped his early personality. He was introspective, curious, and unusually observant—characteristics that would make him one of history’s most visionary architects.

Arrival in Barcelona: A City in Transformation

In 1868, at the age of 16, Gaudí moved to Barcelona with his older brother Francesc to pursue his education. He arrived in a city on the brink of reinvention. The Catalan capital was transforming due to the Industrial Revolution, drawing in workers, thinkers, and artists alike. Barcelona was also experiencing a cultural revival known as La Renaixença, which aimed to elevate the Catalan language and identity. This fusion of tradition and modernity would leave a lasting impression on Gaudí’s worldview.

He settled in the vibrant neighborhood of La Ribera, where narrow medieval streets met the expanding modern grid of the Eixample, planned by Ildefons Cerdà. The young Gaudí roamed through construction sites and burgeoning avenues, absorbing the pulse of a city in motion. “Barcelona needs architects,” he once wrote to a friend, expressing his desire to be part of its rebirth. The evolving city offered fertile ground for Gaudí’s growing ambition to merge functionality, culture, and beauty in urban life.

He saw architecture not merely as a technical discipline but as a means of societal progress and spiritual elevation. These formative experiences in a rapidly modernizing Barcelona helped solidify his belief that architecture should respond not only to human needs but also to the natural and cultural environment. As he would later put it,

“Architecture is the arrangement of light; it is the play of volumes brought together in light.”

The University Years: The Making of a Genius

In 1874, Gaudí entered the Escola Tècnica Superior d’Arquitectura in Barcelona. He was not the most conventional student, often clashing with teachers and following his own instincts. Yet he excelled in drawing, geometry, and history. He also took elective courses in aesthetics, French, and economics, reflecting his belief that an architect should be a polymath. His academic years were fertile ground for experimentation and exploration.

Gaudí’s early projects from this period include visionary but unbuilt proposals like a pavilion for the 1876 Philadelphia World’s Fair, a monumental fountain for Plaça de Catalunya, and several inventive furniture designs. These works already showed signs of his rebellious creativity and preference for merging functionality with beauty.

When he finally graduated in 1878, the director of the school, Elies Rogent, famously said:

“We have either given a diploma to a madman or to a genius.”

That same year, Gaudí opened his first architectural studio at Carrer del Call, No. 11, in Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter. His first commissions were modest: the design of streetlights for Plaça Reial, a display cabinet for the glove shop Comella, and urban planning contributions to Mataró’s workers’ cooperative.

But everything changed when one of his designs—the ornate glass display case for Comella—was exhibited at the Paris World Exposition. It caught the attention of industrial magnate Eusebi Güell, sparking a patronage and friendship that would alter the course of Gaudí’s life.

The Güell Connection: Patron and Friend

In 1878, Gaudí’s life took a dramatic turn when he met Eusebi Güell i Bacigalupi, a wealthy industrialist and influential patron of the arts. Güell had seen Gaudí’s display cabinet for the Comella Glove Company at the Paris World Exposition and was instantly captivated by its originality. Their meeting marked the beginning of a profound professional collaboration and personal friendship that would span decades.

“Gaudí had genius and I had money,” Güell later said. “It was only natural that we work together.”

The first major project Güell entrusted to Gaudí was the Finca Güell (1884–1887), a private estate on the outskirts of Barcelona. There, Gaudí created elaborate gates with a spectacular wrought iron dragon inspired by the myth of the Garden of the Hesperides. The design blended industrial materials and mythological themes—a hallmark of Gaudí’s style. It was a bold statement: art could emerge from utility, and symbolism could reside in function.

First Masterpieces: Casa Vicens and El Capricho

Even before the Finca Güell, Gaudí had begun crafting his personal style. His first major commission came in 1883 from Manuel Vicens i Montaner, a tile manufacturer. The result was Casa Vicens, built between 1883 and 1885 in the Gràcia district of Barcelona. It was unlike anything the city had seen: a house that married Oriental influences with traditional Catalan materials, covered in bold green-and-white ceramic tiles and elaborate wrought iron balconies.

“When I went to take measurements of the plot, it was covered in small yellow flowers,” Gaudí explained. “I took them as the theme for the decorative tiles.”

Casa Vicens blended Spanish Mudejar, Indian, and Islamic motifs, expressed through a riot of color and form. Though it was Gaudí’s first house, it already showed his trademark synthesis of structure, symbolism, and nature. Its vibrant façades, floral ornamentation, and hand-crafted details declared Gaudí’s rebellion against academic architectural conventions. The building earned him his first real recognition as a singular creative force.

That same year, Gaudí received another commission in Comillas, Cantabria. A music-loving lawyer named Máximo Díaz de Quijano asked for a summer home, which would become El Capricho (1883–1885). The house was small but packed with personality: it had oriental-inspired domes, sunflower-themed ceramic tiles, and even musical motifs in the stained glass. Gaudí designed an innovative mechanism in the windows so they played music when opened or closed—a poetic homage to his client’s love of sound.

With these two houses, Gaudí established the core of his early architectural language: a fusion of nature, ornament, and eclectic references. They marked the beginning of his journey toward creating buildings that were not merely functional, but experiences in themselves.

Redefining Gothic: Palau Güell and Colegio Teresiano

Gaudí respected historical architecture, especially the Gothic, but he refused to imitate it blindly.

“The Gothic style is not perfect,” he said. “It is only a half-evolved solution.”

Instead, he sought to reinvent it. This ambition is most evident in the Palau Güell and the Col·legi de les Teresianes, where he balanced tradition with bold innovation.

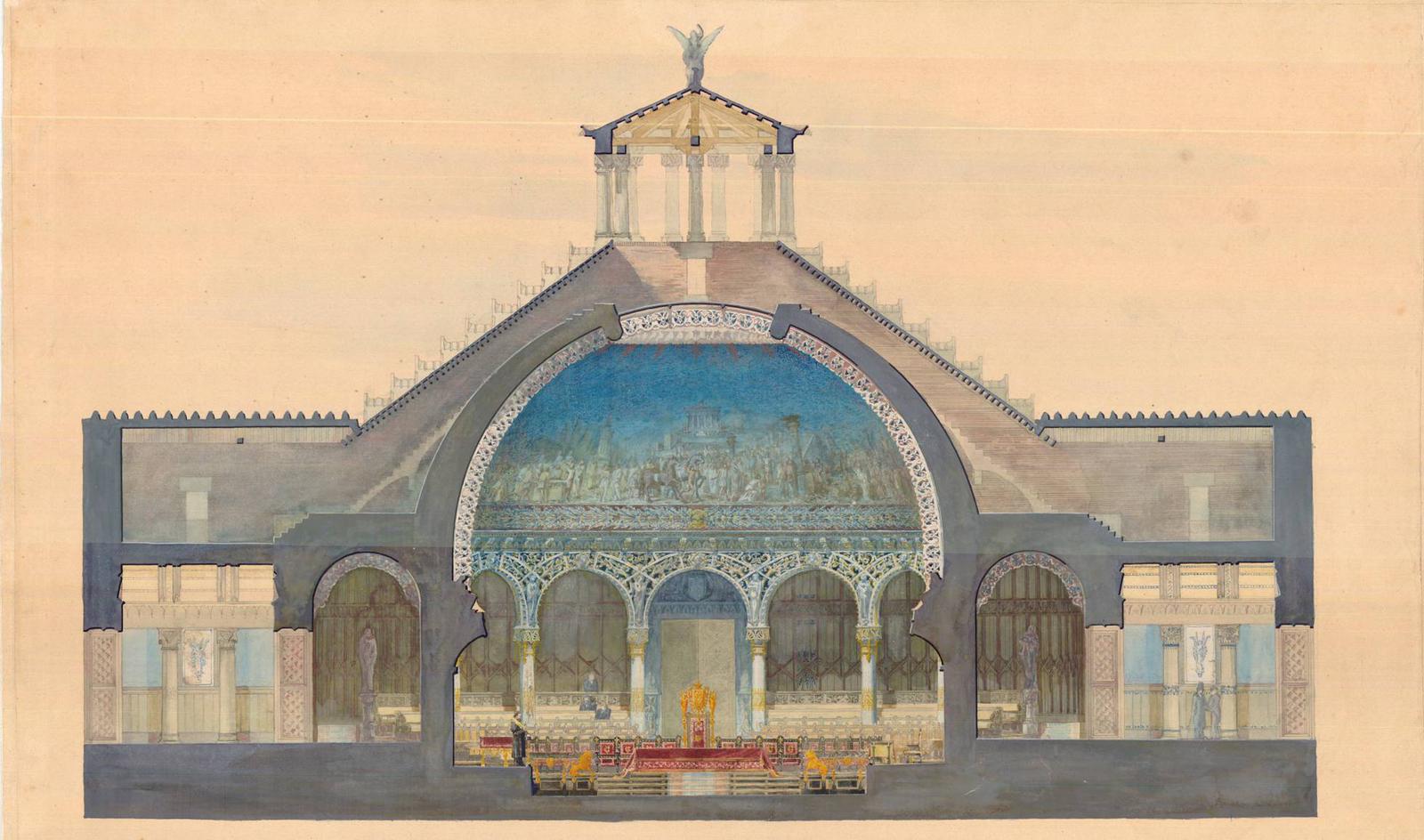

The Palau Güell (1886–1888), while grounded in Gothic inspiration, broke boundaries. Its central salon was a marvel: a vertical space crowned with a dome that filtered natural light like stars in a night sky. The building was both monumental and intimate. Every surface, from ceilings to iron grilles, was a canvas for symbolic meaning and artisan excellence. Here, Gaudí mastered his use of parabolic arches and intricate ironwork, creating a stage for both aesthetics and spiritual elevation.

In 1888, he began designing the Col·legi de les Teresianes in the Sant Gervasi district of Barcelona. Commissioned by the Catholic Order of Saint Teresa of Jesus, the school needed to reflect religious devotion, modesty, and resilience. Gaudí responded with an austere brick structure featuring crenellations, pointed arches, and a fortress-like presence. He described it as a representation of the “interior castle” described by Saint Teresa—a metaphor for spiritual introspection.

The most striking element was the use of long parabolic corridors, where light and shadow danced between arcades, producing a serene rhythm that evoked monastic contemplation. Though simple in materials, the school’s structure was radical in its engineering and spiritual in its essence. It confirmed that Gaudí was not only an artist but a builder of meaning.

Beyond Catalonia: The Northern Fortresses

While most of Gaudí’s works are clustered in Catalonia, he also left his mark further north in Spain, particularly in León and Astorga. These projects reflect his ability to adapt his vision to different climates, landscapes, and historical contexts, while maintaining his unmistakable style.

In 1887, Gaudí received a commission from the Diocese of Astorga to design the Palacio Episcopal (Episcopal Palace), following the destruction of the original structure by fire. Construction began in 1889. Gaudí envisioned a castle that embodied both spiritual grandeur and medieval defense, symbolizing the triumph of Christianity over paganism. The result was a granite monument with neo-Gothic influences: pointed arches, lancet windows, and slender towers. Despite the rigid appearance, the interior is luminous and fluid—two of Gaudí’s core principles. He used innovative materials and construction techniques that allowed the light to play on the vaulted ceilings, enhancing the sacred ambiance.

Unfortunately, due to disagreements with the diocesan council, Gaudí resigned from the project in 1893 before its completion. Yet the three floors he did design clearly show his architectural maturity: bold, symbolic, and spiritual, yet grounded in local tradition and geology.

Meanwhile, in León, Gaudí was commissioned by the textile company Fernández y Andrés to design a mixed-use building that combined residential and commercial spaces. The result was Casa Botines (1891–1892), a neo-Gothic structure with angular towers and defensive façades that recalled medieval fortresses. The foundation, made of traditional Catalan mampostería hormigonada (rubble masonry with concrete), caused concern among local engineers. When told it was structurally unsound, Gaudí responded coolly:

“Let them send me their reports in writing, and I will frame them in the entrance hall once the house is finished.”

Casa Botines, with its sharp geometry and delicate stained glass, illustrates how Gaudí merged practicality with poetic defiance. Both buildings outside Catalonia demonstrate how his vision was not confined by geography—it was universal.

Dragons and Symbolism: A Mystical Language

Gaudí was deeply spiritual and symbolic. His works abound with Christian iconography, but also with mythological and natural motifs—none more prominent than the figure of the dragon. Dragons appear in several of his buildings, serving both decorative and metaphysical purposes. They symbolize danger, wisdom, transformation, and protection, depending on the context and cultural lens.

At Finca Güell (1884–1887), the grand wrought-iron gate features a dragon with a coiled tail and menacing open mouth. It represents the creature from the Garden of the Hesperides, which Hercules had to defeat to retrieve the golden apples. The iron used for the dragon was repurposed industrial material, bent and forged into intricate curves. This was one of Gaudí’s earliest examples of upcycling—turning industrial waste into high art.

At Bellesguard (1900–1909), a lesser-known gem in the Sarrià-Sant Gervasi district of Barcelona, Gaudí designed a turreted structure that from afar resembles a dragon. The tiles on the roof simulate dragon scales, and its architectural layout suggests the body of the beast with its tail rise as tall as its spire. The symbolism here is complex: a tribute to King Martin of Aragon who once lived on the site, and a reference to Catalan folklore and identity.

But perhaps the most famous example is the rooftop of Casa Batlló (1904–1906), where the undulating form mimics the spine of a dragon. Its colorful ceramic tiles resemble scales, and the cross on the rooftop evokes the sword of Saint George piercing the beast. Here, Gaudí blends myth, religion, and architecture seamlessly. He once stated:

“Fantasy and reality are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they need each other.”

Dragons for Gaudí were not just artistic flourishes—they were metaphors for inner struggle, transformation, and spiritual guardianship.

Organic Architecture: Park Güell and Jardín Artigas

By the turn of the century, Gaudí had moved decisively toward organic architecture. No longer content to merely decorate façades, he sought to integrate buildings into the natural landscape so completely that they seemed to grow from the earth itself. Two of his most emblematic projects during this phase are Park Güell (1900–1914) in Barcelona and Jardín Artigas (1905–1906) in La Pobla de Lillet.

Park Güell was originally conceived as a luxury residential estate for Barcelona’s elite, commissioned by Eusebi Güell. Though the plan to sell lots failed, what remained was a fantastical public park filled with curving viaducts, organic columns, and mosaic-covered sculptures. The entrance pavilions resemble gingerbread houses. The staircase features the iconic mosaic salamander—believed to be either a representation of the fire-aligned alchemical symbol or the mythological dragon Piton.

The park’s surface is adorned with trencadís—Gaudí’s now-famous mosaic technique using broken ceramic tiles. When asked about its chaotic nature, Gaudí once grabbed a tile and a flowerpot, smashed them, and exclaimed,

“By the handful! Otherwise, we’ll never finish!”

The result is a dreamscape where architecture becomes a living, breathing extension of the hillside, mimicking the terrain and native flora.

Jardín Artigas, a lesser-known but equally poetic creation, was designed as a gift to the industrialist Joan Artigas, who had hosted Gaudí during the construction of the nearby Chalet del Catllaràs. Located on the banks of the Llobregat River, the garden incorporates bridges, fountains, and caves—constructed using local stone and designed to harmonize with the flowing water. While Park Güell represents controlled nature and urban idealism, Jardín Artigas is wild, fluid, and fully surrendered to the natural course of the river.

In both parks, Gaudí’s genius as a landscape architect shines. He understood not only how to build on land but how to listen to it.

“There are no straight lines or sharp corners in nature,” he said. “Therefore, buildings must have no straight lines or sharp corners.”

Casa Batlló: A Marine Symphony in Stone

By the early 20th century, Gaudí had matured into a fully developed master of his own architectural language. One of the most striking examples of this is Casa Batlló, redesigned between 1904 and 1906. Located on the prestigious Passeig de Gràcia in Barcelona, the building is a radical reworking of a previously conventional home. Commissioned by industrialist Josep Batlló, the result was a fantastical structure inspired by the sea, myth, and organic life forms.

From the outside, Casa Batlló evokes the scales of a great marine creature. The façade is a shimmering wave of colored glass and ceramic tiles in aquatic tones of blue, green, and lilac. The balconies resemble the jaws of sea creatures or perhaps bones, earning the building the nickname “House of Bones.” The rooftop mimics the arched back of a dragon, its ridge tiled in scaly trencadís, with a turreted cross interpreted as Saint George’s sword striking down the beast.

Inside, the building is no less fantastical. Gaudí restructured the interior around a central light well, widening windows as they descended to allow for equal light distribution—an ingenious solution to maximize natural illumination. He even used varying shades of blue tiles, lighter at the bottom and darker at the top, to create a seamless gradient of color and brightness. The attic, with its parabolic arches, evokes the ribcage of a whale—another subtle marine metaphor. As Gaudí often said,

“The straight line belongs to men, the curved line to God.”

Casa Batlló is more than a home—it’s a total work of art. Every detail, from doorknobs molded to the human hand to the organic curves of the staircases, demonstrates Gaudí’s belief in ergonomic and artistic harmony. He designed not only the architecture but the furniture and décor, unifying the space as a complete living sculpture. The house is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of Barcelona’s most beloved attractions.

La Pedrera: Fluid Forms and Functional Innovation

From 1906 to 1912, Gaudí worked on another revolutionary project: Casa Milà, more commonly known as La Pedrera (meaning “The Stone Quarry”). Commissioned by Pere Milà and Roser Segimon, this was Gaudí’s last private civil work and arguably one of his most experimental. At the time, it was highly controversial. Critics mocked its undulating stone façade and unconventional layout, but today it is considered a masterpiece of modernist architecture.

Gaudí broke from tradition entirely with La Pedrera. The building lacks structural walls—instead, it uses a system of columns and beams that allowed for open, adaptable floor plans, decades ahead of its time. The curved exterior mimics the waves of the sea, while the wrought iron balconies appear as twisting vines or seaweed, fashioned from scrap metal by blacksmith Josep Maria Jujol. Every part of the structure was handcrafted, down to the irregularly shaped windows and ornamental carvings.

The rooftop is perhaps its most iconic feature: a surreal landscape of sculptural chimneys and ventilation towers, some over seven meters tall. Their eerie, helmeted shapes have been compared to warriors or surreal chess pieces. Gaudí treated the roof not as an afterthought but as a public space—an extension of the building’s artistic and symbolic language.

Inside, the building is equally radical. Two massive interior courtyards bring light and air to every unit. The doors and gates are designed with ergonomic fluidity, and the forged iron main entrance draws inspiration from sea shells and tortoise shells. Gaudí also incorporated an underground garage—a revolutionary concept for the early 20th century.

.jpg)

Despite the criticism it initially received, Gaudí remained firm in his vision.

“There is no reason not to try new things,” he insisted.

Today, La Pedrera is a UNESCO-listed site and a shining example of how architectural form can be both beautiful and profoundly functional.

Cripta Güell: Gaudí’s Lab of Innovation

Between 1898 and 1914, Gaudí developed the Cripta Güell (Crypt of the Güell Colony), an architectural laboratory nestled in the industrial town of Santa Coloma de Cervelló. Commissioned by Eusebi Güell to serve as a church for the workers of his textile colony, the Cripta was never completed, but its importance cannot be overstated. It is here that Gaudí tested many of the structural and aesthetic techniques that would later culminate in the Sagrada Familia.

The Cripta Güell features inclined and twisted columns made from basalt and brick, forming parabolic arches that create a forest-like atmosphere inside. The church was partially embedded in a hillside, requiring Gaudí to adapt to the natural slope—a challenge he turned into an opportunity for creative brilliance. The architecture responds to the terrain like a living organism, with curving lines and organic transitions between floor levels.

One of the most groundbreaking techniques Gaudí developed here was the use of maqueta funicular—a hanging chain model to determine the most efficient load-bearing structure. He would suspend strings with weights and observe how they naturally formed parabolas under gravity. By inverting the model, he obtained the optimal shapes for his arches and vaults.

"I calculate everything,” Gaudí said. “First, I hang strings to find the funicular; then I test and retest until the final form is a logical consequence of its structure.”

The materials used in the Cripta were humble—recycled wood, iron, bricks, and natural stone. Yet Gaudí transformed them into a mystical, meditative space. Benches crafted from repurposed shipping crates, iron railings mimicking vines, and windows that cast kaleidoscopic light create a sacred and intimate atmosphere. The columns themselves were color-coded: black basalt to evoke the forest floor, and reddish brick to resemble pine trunks. The church’s unfinished state gives it a rawness that makes its brilliance even more tangible.

The Cripta Güell was not just a place of worship; it was a crucible of innovation. It offered Gaudí the chance to test and refine the ideas that would one day shape his magnum opus: the Sagrada Familia.

Sagrada Familia: The Temple of a Lifetime

In 1883, Antoni Gaudí accepted a commission that would become the defining project of his life: the Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família (Expiatory Temple of the Holy Family). Initially begun under another architect, Gaudí took over the project at age 31 and transformed it into a spiritual and architectural manifesto that embodied all his beliefs, techniques, and aesthetic principles.

From 1914 onward, Gaudí ceased accepting other commissions to dedicate himself fully to the Sagrada Familia. He moved into a small workshop next to the site, where he lived and worked obsessively until his death in 1926.

“My client is in no hurry,”

he would say, referring to God and the slow progress of the temple. His vision was so vast that he knew it would not be completed within his lifetime. Yet he left detailed drawings, models, and instructions for future architects to continue the work.

The Sagrada Familia fuses Gothic and Art Nouveau with Gaudí’s own innovations. Its interior resembles a vast forest: slender, branching columns mimic tree trunks rising to a canopy of stone. The vaults are covered in geometric patterns, and the natural light streaming through the stained-glass windows creates a kaleidoscopic atmosphere that evokes awe and spiritual elevation.

“The structure of the Sagrada Familia is like a tree,” Gaudí said, “with trunks, branches and foliage. A temple of nature, reaching to heaven.”

Structurally, Gaudí used the techniques he pioneered in the Cripta Güell—parabolic arches, funicular modeling, and a hyperboloid geometry that gave strength without mass. Symbolically, every detail is imbued with meaning: the Nativity façade celebrates life and creation; the Passion façade is austere and dramatic, depicting Christ’s suffering; and the Glory façade (still under construction) will represent resurrection and transcendence. The 18 spires, when complete, will honor the 12 apostles, 4 evangelists, the Virgin Mary, and Jesus Christ, the tallest reaching 172.5 meters, just shy of Montjuïc hill—because, Gaudí said,

“Man’s work should not exceed God’s.”

Despite being unfinished at the time of his death, Gaudí’s spiritual and artistic blueprint remains intact. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site and consecrated as a minor basilica by Pope Benedict XVI in 2010, the Sagrada Familia is expected to be completed by 2026, to mark the centenary of Gaudí’s passing. It is the most visited monument in Spain and a beacon of sacred modern architecture.

Legacy: The Global Artist of Nature and Faith

Antoni Gaudí died on June 10, 1926, after being struck by a tram three days earlier at the intersection of Gran Via and Carrer de Bailèn in Barcelona. Disheveled and carrying no identification—only a rosary, a gospel, some hazelnuts, and a mysterious key—he was initially mistaken for a beggar. Once identified, all of Barcelona mourned the loss of the man who had given the city its most extraordinary architectural jewels.

He was buried in the crypt of the Sagrada Familia, beneath the altar of the chapel of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. It was a quiet end for a man whose work continues to echo through the world’s skylines and hearts. Though Gaudí left behind few writings, his buildings speak volumes. They are temples of imagination, science, and faith. He is often seen as the father of “total architecture”—where structure, function, decoration, and symbolism exist as one.

Gaudí’s influence extends far beyond Catalonia. Architects, urbanists, and artists across the globe continue to draw inspiration from his innovative methods and spiritual philosophy. His commitment to integrating nature into design anticipated ecological and sustainable architecture by decades. And his belief in beauty as a path to God still resonates in a world searching for deeper meaning.

Gaudí’s legacy is also institutional: several of his works, including Casa Batlló, Casa Vicens, Palau Güell, Park Güell, and La Pedrera, have been designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites. In 2003, the Vatican began the process of canonizing him, and in 2010, he was declared a Servant of God—a step toward sainthood. For many, Gaudí is not only a genius but a holy man of architecture.

Conclusion: Gaudí’s Genius Lives On

Antoni Gaudí did not merely construct buildings—he constructed visions, myths, and worlds in stone. He was a dreamer, an alchemist, and a revolutionary who blended the mystical with the mathematical, the organic with the divine. In a time of industrialization and mass production, he turned back to craftsmanship, to the irregular perfection of nature, and to the eternal truths of faith.

“To do things right,” he said, “first you need love, then technique.”

His buildings are more than monuments; they are experiences that invite reflection, wonder, and transcendence. From the colorful tiles of Park Güell to the sacred geometry of the Sagrada Familia, Gaudí’s work continues to guide those who believe architecture is more than shelter—it is art, spirit, and soul made manifest.

Nearly a century after his death, Antoni Gaudí remains a singular figure in world architecture. His genius lives on—not just in stone, but in the hearts of those moved by the beauty he left behind.